in gullivers travels, what are the lilliputians quarreling about that leads to war?

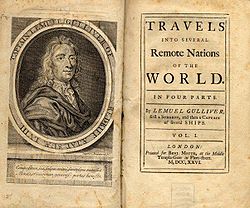

First edition of Gulliver'southward Travels | |

| Author | Jonathan Swift |

|---|---|

| Original championship | Travels into Several Remote Nations of the Earth. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, Start a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships |

| State | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Satire, fantasy |

| Publisher | Benjamin Motte |

| Publication engagement | 28 October 1726 (1726-10-28) |

| Media type | |

| Dewey Decimal | 823.five |

| Text | Gulliver's Travels at Wikisource |

Gulliver'southward Travels , or Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, Starting time a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships is a 1726 prose satire[1] [2] by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift, satirising both man nature and the "travellers' tales" literary subgenre. It is Swift's all-time known full-length work, and a archetype of English literature. Swift claimed that he wrote Gulliver's Travels "to vex the world rather than divert it".

The volume was an firsthand success. The English dramatist John Gay remarked "It is universally read, from the chiffonier quango to the nursery."[3] In 2015, Robert McCrum released his selection listing of 100 best novels of all time in which Gulliver's Travels is listed as "a satirical masterpiece".[4]

Plot [edit]

Locations visited by Gulliver, according to Arthur Ellicott Case. Case contends that the maps in the published text were drawn by someone who did not follow Swift'southward geographical descriptions; to correct this, he makes changes such equally placing Lilliput to the east of Australia instead of the west. [5]

Part I: A Voyage to Lilliput [edit]

Mural depicting Gulliver surrounded past citizens of Lilliput.

The travel begins with a short preamble in which Lemuel Gulliver gives a brief outline of his life and history earlier his voyages.

- iv May 1699 – 13 Apr 1702

During his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and finds himself a prisoner of a race of tiny people, less than 6 inches (15 cm) tall, who are inhabitants of the island country of Lilliput. Subsequently giving assurances of his practiced behaviour, he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the Lilliput Royal Court. He is also given permission by the King of Lilliput to become around the city on condition that he must not hurt their subjects.

At kickoff, the Lilliputians are hospitable to Gulliver, but they are likewise wary of the threat that his size poses to them. The Lilliputians reveal themselves to exist a people who put great emphasis on footling matters. For instance, which terminate of an egg a person cracks becomes the basis of a deep political rift within that nation. They are a people who revel in displays of authorisation and performances of ability. Gulliver assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours the Blefuscudians by stealing their fleet. Withal, he refuses to reduce the isle nation of Blefuscu to a province of Lilliput, displeasing the King and the royal court.

Gulliver is charged with treason for, among other crimes, urinating in the capital though he was putting out a fire. He is convicted and sentenced to be blinded. With the assistance of a kind friend, "a considerable person at courtroom", he escapes to Blefuscu. Here, he spots and retrieves an abandoned boat and sails out to exist rescued by a passing ship, which safely takes him back home with some Footling animals he carries with him.

Function II: A Voyage to Brobdingnag [edit]

- 20 June 1702 – iii June 1706

Gulliver soon sets out again. When the sailing ship Run a risk is blown off course past storms and forced to canvass for land in search of fresh water, Gulliver is abased past his companions and left on a peninsula on the western declension of the North American continent.

The grass of Brobdingnag is as tall equally a tree. He is and then institute by a farmer who is about 72 ft (22 chiliad) tall, judging from Gulliver estimating the man's step being ten yards (9 m). The giant farmer brings Gulliver habitation, and his girl Glumdalclitch cares for Gulliver. The farmer treats him as a curiosity and exhibits him for money. Subsequently a while the constant display makes Gulliver sick, and the farmer sells him to the queen of the realm. Glumdalclitch (who accompanied her father while exhibiting Gulliver) is taken into the queen's service to have intendance of the tiny man. Since Gulliver is too pocket-size to utilize their huge chairs, beds, knives and forks, the queen commissions a small house to exist built for him and then that he can be carried effectually in information technology; this is referred to as his "travelling box".

Betwixt modest adventures such as fighting giant wasps and beingness carried to the roof past a monkey, he discusses the state of Europe with the Rex of Brobdingnag. The male monarch is not happy with Gulliver's accounts of Europe, especially upon learning of the employ of guns and cannon. On a trip to the seaside, his traveling box is seized by a behemothic eagle which drops Gulliver and his box into the sea where he is picked up by sailors who return him to England.

Function III: A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib and Japan [edit]

Gulliver discovers Laputa, the floating/flying island (illustration by J. J. Grandville)

- v August 1706 – sixteen April 1710

Setting out again, Gulliver's ship is attacked by pirates, and he is marooned close to a desolate rocky isle nearly Republic of india. He is rescued by the flying isle of Laputa, a kingdom devoted to the arts of music, mathematics, and astronomy merely unable to employ them for practical ends. Rather than using armies, Laputa has a custom of throwing rocks down at rebellious cities on the ground.

Gulliver tours Balnibarbi, the kingdom ruled from Laputa, equally the invitee of a low-ranking courtier and sees the ruin brought about by the blind pursuit of scientific discipline without applied results, in a satire on hierarchy and on the Royal Society and its experiments. At the M Academy of Lagado in Balnibarbi, neat resources and manpower are employed on researching preposterous schemes such equally extracting sunbeams from cucumbers, softening marble for use in pillows, learning how to mix paint by odour, and uncovering political conspiracies by examining the excrement of suspicious persons (see muckraking). Gulliver is then taken to Maldonada, the master port of Balnibarbi, to await a trader who tin can take him on to Japan.

While waiting for a passage, Gulliver takes a brusque side-trip to the isle of Glubbdubdrib which is southwest of Balnibarbi. On Glubbdubdrib, he visits a wizard's dwelling and discusses history with the ghosts of historical figures, the well-nigh obvious restatement of the "ancients versus moderns" theme in the book. The ghosts include Julius Caesar, Brutus, Homer, Aristotle, René Descartes, and Pierre Gassendi.

On the island of Luggnagg, he encounters the struldbrugs, people who are immortal. They do not have the gift of eternal youth, but suffer the infirmities of onetime age and are considered legally expressionless at the historic period of eighty.

Afterwards reaching Nippon, Gulliver asks the Emperor "to excuse my performing the ceremony imposed upon my countrymen of trampling upon the crucifix", which the Emperor does. Gulliver returns home, determined to stay there for the remainder of his days.

Part IV: A Voyage to the Land of the Houyhnhnms [edit]

Gulliver in give-and-take with Houyhnhnms (1856 illustration past J.J. Grandville).

- 7 September 1710 – 5 December 1715

Despite his before intention of remaining at home, Gulliver returns to sea as the captain of a merchantman, as he is bored with his employment every bit a surgeon. On this voyage, he is forced to find new additions to his coiffure who, he believes, have turned against him. His crew then commits mutiny. After keeping him contained for some time, they resolve to go out him on the first piece of country they come across, and continue as pirates. He is abandoned in a landing boat and comes upon a race of plain-featured savage humanoid creatures to which he conceives a violent antipathy. Soon afterwards, he meets the Houyhnhnms, a race of talking horses. They are the rulers while the deformed creatures that resemble human being beings are chosen Yahoos.

Gulliver becomes a member of a horse's household and comes to both admire and emulate the Houyhnhnms and their manner of life, rejecting his fellow humans as merely Yahoos endowed with some semblance of reason which they only utilize to exacerbate and add together to the vices Nature gave them. However, an Assembly of the Houyhnhnms rules that Gulliver, a Yahoo with some semblance of reason, is a danger to their civilization and commands him to swim back to the land that he came from. Gulliver's "Master," the Houyhnhnm who took him into his household, buys him time to create a canoe to brand his departure easier. After some other disastrous voyage, he is rescued against his will past a Portuguese ship. He is disgusted to come across that Helm Pedro de Mendez, whom he considers a Yahoo, is a wise, courteous, and generous person.

He returns to his abode in England, but is unable to reconcile himself to living among "Yahoos" and becomes a recluse, remaining in his firm, avoiding his family and his wife, and spending several hours a twenty-four hour period speaking with the horses in his stables.

Composition and history [edit]

It is uncertain exactly when Swift started writing Gulliver's Travels. (Much of the writing was done at Loughry Manor in Cookstown, County Tyrone, whilst Swift stayed there.) Some sources[ which? ] suggest as early as 1713 when Swift, Gay, Pope, Arbuthnot and others formed the Scriblerus Club with the aim of satirising popular literary genres. [6]According to these accounts, Swift was charged with writing the memoirs of the club's imaginary author, Martinus Scriblerus, and as well with satirising the "travellers' tales" literary subgenre. It is known from Swift's correspondence that the limerick proper began in 1720 with the mirror-themed Parts I and Two written first, Part IV side by side in 1723 and Part Three written in 1724; merely amendments were fabricated even while Swift was writing Drapier'southward Letters. By August 1725 the book was complete; and equally Gulliver's Travels was a transparently anti-Whig satire, it is likely that Swift had the manuscript copied and so that his handwriting could non be used as show if a prosecution should arise, as had happened in the case of some of his Irish pamphlets (the Drapier's Letters). In March 1726 Swift travelled to London to have his work published; the manuscript was secretly delivered to the publisher Benjamin Motte, who used five printing houses to speed production and avert piracy.[seven] Motte, recognising a all-time-seller but fearing prosecution, cut or altered the worst offending passages (such every bit the descriptions of the court contests in Lilliput and the rebellion of Lindalino), added some cloth in defence of Queen Anne to Part II, and published it. The beginning edition was released in two volumes on 28 Oct 1726, priced at 8s. 6d. [eight]

Motte published Gulliver's Travels anonymously, and as was often the way with fashionable works, several follow-ups (Memoirs of the Courtroom of Lilliput), parodies (Two Lilliputian Odes, The outset on the Famous Engine With Which Helm Gulliver extinguish'd the Palace Fire...) and "keys" (Gulliver Decipher'd and Lemuel Gulliver's Travels into Several Remote Regions of the World Compendiously Methodiz'd, the second by Edmund Curll who had similarly written a "key" to Swift'south Tale of a Tub in 1705) were swiftly produced. These were by and large printed anonymously (or occasionally pseudonymously) and were quickly forgotten. Swift had nothing to do with them and disavowed them in Faulkner'southward edition of 1735. Swift's friend Alexander Pope wrote a set up of five Verses on Gulliver's Travels, which Swift liked so much that he added them to the second edition of the book, though they are rarely included.

Faulkner's 1735 edition [edit]

In 1735 an Irish publisher, George Faulkner, printed a prepare of Swift'south works, Volume III of which was Gulliver's Travels. Equally revealed in Faulkner'south "Advertisement to the Reader", Faulkner had access to an annotated re-create of Motte's piece of work by "a friend of the writer" (by and large believed to be Swift's friend Charles Ford) which reproduced most of the manuscript without Motte'due south amendments, the original manuscript having been destroyed. Information technology is also believed that Swift at least reviewed proofs of Faulkner's edition before printing, just this cannot be proved. Mostly, this is regarded as the Editio Princeps of Gulliver's Travels with one small exception. This edition had an added slice by Swift, A letter from Capt. Gulliver to his Cousin Sympson, which complained of Motte's alterations to the original text, saying he had so much contradistinct it that "I exercise hardly know mine own work" and repudiating all of Motte'south changes as well every bit all the keys, libels, parodies, second parts and continuations that had appeared in the intervening years. This letter at present forms part of many standard texts.

Lindalino [edit]

The 5-paragraph episode in Part Three, telling of the rebellion of the surface metropolis of Lindalino against the flying island of Laputa, was an obvious allegory to the affair of Drapier'south Letters of which Swift was proud. Lindalino represented Dublin and the impositions of Laputa represented the British imposition of William Wood's poor-quality copper currency. Faulkner had omitted this passage, either because of political sensitivities raised by an Irish publisher printing an anti-British satire, or possibly because the text he worked from did not include the passage. In 1899 the passage was included in a new edition of the Collected Works. Modernistic editions derive from the Faulkner edition with the inclusion of this 1899 addendum.

Isaac Asimov notes in The Annotated Gulliver that Lindalino is generally taken to be Dublin, being equanimous of double lins; hence, Dublin.[nine]

Major themes [edit]

Gulliver's Travels has been the recipient of several designations: from Menippean satire to a children's story, from proto-science fiction to a forerunner of the modernistic novel.

Published 7 years after Daniel Defoe'southward successful Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver's Travels may be read as a systematic rebuttal of Defoe'southward optimistic account of human capability. In The Unthinkable Swift: The Spontaneous Philosophy of a Church of England Man, Warren Montag argues that Swift was concerned to refute the notion that the individual precedes social club, every bit Defoe'due south piece of work seems to advise. Swift regarded such thought equally a unsafe endorsement of Thomas Hobbes' radical political philosophy and for this reason Gulliver repeatedly encounters established societies rather than desolate islands. The captain who invites Gulliver to serve equally a surgeon aboard his transport on the disastrous third voyage is named Robinson.

Scholar Allan Flower asserts that Swift's lampooning of the experiments of Laputa is the first questioning by a mod liberal democrat of the effects and toll on a society which embraces and celebrates policies pursuing scientific progress.[ten] Swift wrote:

The commencement man I saw was of a meagre aspect, with sooty easily and face up, his pilus and bristles long, ragged, and singed in several places. His clothes, shirt, and peel, were all of the same color. He has been 8 years upon a project for extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers, which were to be put in phials hermetically sealed, and let out to warm the air in raw choppy summers. He told me, he did not uncertainty, that, in eight years more, he should be able to supply the governor's gardens with sunshine, at a reasonable charge per unit: merely he complained that his stock was depression, and entreated me "to give him something as an encouragement to ingenuity, especially since this had been a very dear flavor for cucumbers". I made him a small present, for my lord had furnished me with money on purpose, considering he knew their practise of begging from all who go to come across them.

A possible reason for the book's classic status is that information technology can exist seen as many things to many people. Broadly, the volume has three themes:

- A satirical view of the state of European government, and of petty differences between religions

- An inquiry into whether people are inherently decadent or whether they get corrupted

- A restatement of the older "ancients versus moderns" controversy previously addressed by Swift in The Boxing of the Books

In storytelling and construction the parts follow a pattern:

- The causes of Gulliver'due south misadventures become more malignant every bit time goes on—he is kickoff shipwrecked, so abased, then attacked by strangers, then attacked by his ain crew.

- Gulliver's attitude hardens as the book progresses—he is genuinely surprised by the viciousness and politicking of the Lilliputians but finds the behaviour of the Yahoos in the 4th part reflective of the behaviour of people.

- Each office is the reverse of the preceding part—Gulliver is big/small/wise/ignorant, the countries are complex/uncomplicated/scientific/natural, and Gulliver perceives the forms of government as worse/meliorate/worse/better than Britain'southward (although Swift's opinions on this matter are unclear).

- Gulliver's viewpoint betwixt parts is mirrored by that of his antagonists in the contrasting function—Gulliver sees the tiny Lilliputians every bit being vicious and unscrupulous, and then the king of Brobdingnag sees Europe in exactly the same lite; Gulliver sees the Laputians every bit unreasonable, and his Houyhnhnm master sees humanity as equally and so.

- No form of regime is ideal—the simplistic Brobdingnagians enjoy public executions and have streets infested with beggars, the honest and upright Houyhnhnms who take no word for lying are happy to suppress the true nature of Gulliver equally a Yahoo and are equally unconcerned about his reaction to beingness expelled.

- Specific individuals may be good even where the race is bad—Gulliver finds a friend in each of his travels and, despite Gulliver's rejection and horror toward all Yahoos, is treated very well by the Portuguese captain, Don Pedro, who returns him to England at the book's terminate.

Of equal interest is the character of Gulliver himself—he progresses from a cheery optimist at the showtime of the beginning part to the pompous misanthrope of the book'due south conclusion and we may well have to filter our understanding of the work if we are to believe the concluding misanthrope wrote the whole work. In this sense, Gulliver's Travels is a very modern and complex work. There are subtle shifts throughout the book, such as when Gulliver begins to come across all humans, not just those in Houyhnhnm-land, every bit Yahoos.[11]

Throughout, Gulliver is presented as being gullible. He generally accepts what he is told at confront value; he rarely perceives deeper meanings; and he is an honest man who expects others to be honest. This makes for fun and irony: what Gulliver says tin can be trusted to be accurate, and he does not always empathize the pregnant of what he perceives.

Also, although Gulliver is presented as a commonplace "lowest" with only a basic instruction, he possesses a remarkable natural gift for language. He apace becomes fluent in the native tongues of the strange lands in which he finds himself, a literary device that adds verisimilitude and humour to Swift's work.

Despite the depth and subtlety of the book, likewise as frequent off-colour and black humour, it is often mistakenly classified as a children's story because of the popularity of the Lilliput section (frequently bowdlerised) as a book for children. Indeed, many adaptations of the story are squarely aimed at a young audience, and one tin can notwithstanding buy books entitled Gulliver's Travels which contain only parts of the Lilliput voyage, and occasionally the Brobdingnag section.

Misogyny [edit]

Although Swift is often accused of misogyny in this work, many scholars believe Gulliver'due south blatant misogyny to be intentional, and that Swift uses satire to openly mock misogyny throughout the volume. 1 of the most cited examples of this comes from Gulliver'southward description of a Brobdingnagian adult female:

I must confess no Object ever disgusted me so much as the Sight of her monstrous Chest, which I cannot tell what to compare with, and so as to give the curious Reader an Thought of its Bulk, Shape, and Colour.... This fabricated me reflect upon the off-white Skins of our English Ladies, who appear so beautiful to usa, simply because they are of our own Size, and their Defects not to be seen just through a magnifying drinking glass....

This open critique towards aspects of the female torso is something that Swift ofttimes brings up in other works of his, particularly in poems such as The Lady'southward Dressing Room and A Beautiful Immature Nymph Going To Bed.[12]

A criticism of Swift'southward use of misogyny past Felicity A. Nussbaum proposes the idea that "Gulliver himself is a gendered object of satire, and his antifeminist sentiments may be among those mocked". Gulliver's own masculinity is often mocked, seen in how he is made to be a coward among the Brobdingnag people, repressed past the people of Lilliput, and viewed as an junior Yahoo among the Houyhnhnms.[11]

Nussbaum goes on to say in her analysis of the misogyny of the stories that in the adventures, particularly in the first story, the satire isn't singularly focused on satirizing women, but to satirize Gulliver himself as a politically naive and inept giant whose masculine authority comically seems to be in jeopardy.[13]

Some other criticism of Swift's use of misogyny delves into Gulliver'south repeated apply of the word 'nauseous', and the manner that Gulliver is fighting his emasculation by commenting on how he thinks the women of Brobdingnag are icky.

Swift has Gulliver frequently invoke the sensory (as opposed to reflective) word "nauseous" to describe this and other magnified images in Brobdingnag not only to reveal the neurotic depths of Gulliver's misogyny, but besides to show how male person nausea can be used as a pathetic countermeasure against the perceived threat of female consumption. Swift has Gulliver associate these magnified acts of female consumption with the act of "throwing-up"—the opposite of and antitoxin to the human action of gastronomic consumption.[xiv]

This commentary of Deborah Needleman Armintor relies upon the way that the giant women do with Gulliver every bit they delight, in much the same way equally one might play with a toy, and go information technology to do everything one can retrieve of. Armintor's comparison focuses on the pocket microscopes that were pop in Swift'south fourth dimension. She talks virtually how this instrument of science was transitioned to something toy-like and accessible, then information technology shifted into something that women favored, and thus men lost interest. This is like to the progression of Gulliver'south time in Brobdingnag, from man of science to women's plaything.

Comic misanthropy [edit]

Misanthropy is a theme that scholars have identified in Gulliver'southward Travels. Arthur Instance, R.Southward. Crane, and Edward Stone discuss Gulliver's development of misanthropy and come up to the consensus that this theme ought to exist viewed as comical rather than cynical.[xv] [sixteen] [17]

In terms of Gulliver's evolution of misanthropy, these three scholars indicate to the fourth voyage. According to Case, Gulliver is at first balky to identifying with the Yahoos, but, afterward he deems the Houyhnhnms superior, he comes to believe that humans (including his fellow Europeans) are Yahoos due to their shortcomings. Perceiving the Houyhnhnms as perfect, Gulliver thus begins to perceive himself and the rest of humanity as imperfect.[xv] Co-ordinate to Crane, when Gulliver develops his misanthropic mindset, he becomes ashamed of humans and views them more than in line with animals.[xvi] This new perception of Gulliver's, Rock claims, comes about because the Houyhnhnms' sentence pushes Gulliver to identify with the Yahoos.[17] Along like lines, Crane holds that Gulliver's misanthropy is developed in part when he talks to the Houyhnhnms almost mankind because the discussions lead him to reverberate on his previously held notion of humanity. Specifically, Gulliver's master, who is a Houyhnhnm, provides questions and commentary that contribute to Gulliver'due south reflectiveness and subsequent development of misanthropy.[16] However, Example points out that Gulliver's dwindling opinion of humans may be blown out of proportion due to the fact that he is no longer able to see the expert qualities that humans are capable of possessing. Gulliver's new view of humanity, then, creates his repulsive attitude towards his fellow humans after leaving Houyhnhnmland.[15] Merely in Rock'southward view, Gulliver's actions and attitude upon his return can exist interpreted equally misanthropy that is exaggerated for comic consequence rather than for a contemptuous effect. Stone further suggests that Gulliver goes mentally mad and believes that this is what leads Gulliver to exaggerate the shortcomings of humankind.[17]

Another aspect that Crane attributes to Gulliver'southward evolution of misanthropy is that when in Houyhnhnmland, it is the animal-like beings (the Houyhnhnms) who exhibit reason and the human-similar beings (the Yahoos) who seem devoid of reason; Crane argues that it is this switch from Gulliver's perceived norm that leads the mode for him to question his view of humanity. As a result, Gulliver begins to identify humans every bit a type of Yahoo. To this indicate, Crane brings up the fact that a traditional definition of man—Human est animal rationale (Humans are rational animals)—was prominent in academia around Swift'southward time. Furthermore, Crane argues that Swift had to study this type of logic (see Porphyrian Tree) in higher, so it is highly likely that he intentionally inverted this logic past placing the typically given example of irrational beings—horses—in the place of humans and vice versa.[16]

Stone points out that Gulliver's Travels takes a cue from the genre of the travel book, which was pop during Swift's time flow. From reading travel books, Swift's contemporaries were accustomed to beast-like figures of strange places; thus, Stone holds that the creation of the Yahoos was not out of the ordinary for the time period. From this playing off of familiar genre expectations, Stone deduces that the parallels that Swift draws between the Yahoos and humans is meant to be humorous rather than cynical. Fifty-fifty though Gulliver sees Yahoos and humans as if they are one and the same, Stone argues that Swift did non intend for readers to take on Gulliver's view; Stone states that the Yahoos' behaviors and characteristics that ready them autonomously from humans farther supports the notion that Gulliver's identification with Yahoos is not meant to be taken to heart. Thus, Stone sees Gulliver's perceived superiority of the Houyhnhnms and subsequent misanthropy as features that Swift used to employ the satirical and humorous elements feature of the Beast Fables of travel books that were popular with his contemporaries; every bit Swift did, these Fauna Fables placed animals above humans in terms of morals and reason, simply they were not meant to exist taken literally.[17]

Character analysis [edit]

Pedro de Mendez is the name of the Portuguese captain who rescues Gulliver in Book IV. When Gulliver is forced to get out the Island of the Houyhnhnms, his programme is "to discover some minor Island uninhabited" where he tin live in confinement. Instead, he is picked upward past Don Pedro'due south crew. Despite Gulliver's appearance—he is dressed in skins and speaks similar a equus caballus—Don Pedro treats him compassionately and returns him to Lisbon.

Though Don Pedro appears but briefly, he has become an important figure in the fence between and so-called soft school and hard school readers of Gulliver's Travels. Some critics debate that Gulliver is a target of Swift'southward satire and that Don Pedro represents an ideal of human kindness and generosity. Gulliver believes humans are similar to Yahoos in the sense that they make "no other use of reason, than to improve and multiply ... vices".[eighteen] Captain Pedro provides a contrast to Gulliver's reasoning, proving humans are able to reason, exist kind, and most of all: civilized. Gulliver sees the dour fallenness at the center of human nature, and Don Pedro is merely a pocket-sized character who, in Gulliver's words, is "an Animate being which had some little Portion of Reason".[xix]

Political allusions [edit]

While we cannot make assumptions well-nigh Swift's intentions, office of what makes his writing so engaging throughout time is speculating the diverse political allusions within it. These allusions tend to become in and out of fashion, but here are some of the common (or merely interesting) allusions asserted by Swiftian scholars. Part I is probably responsible for the greatest number of political allusions, ranging from consistent allegory to minute comparisons. I of the most commonly noted parallels is that the wars between Lilliput and Blefuscu resemble those between England and French republic.[20] The enmity between the low heels and the high heels is often interpreted as a parody of the Whigs and Tories, and the character referred to as Flimnap is often interpreted every bit an allusion to Sir Robert Walpole, a British statesman and Whig politician who Swift had a personally turbulent human relationship with.

In Part Three, the chiliad University of Lagado in Balnibarbi resembles and satirizes the Royal Club, which Swift was openly critical of. Furthermore, "A.E. Example, interim on a tipoff offered by the word 'projectors,' found [the Academy] to be the hiding place of many of those speculators implicated in the Due south Body of water Bubble."[21] According to Treadwell, however, these implications extend beyond the speculators of the South Ocean Bubble to include the many projectors of the belatedly seventeenth and early eighteenth century England, including Swift himself. Not only is Swift satirizing the role of the projector in contemporary English politics, which he dabbled in during his younger years, but the function of the satirist, whose goals align with that of a projector: "The less obvious corollary of that give-and-take [projector] is that it must include the poor deluded satirist himself, since satire is, in its very essence, the wildest of all projects - a scheme to reform the world."[21]

Ann Kelly describes Part Four of The Travels and the Yahoo-Houyhnhnm human relationship every bit an allusion to that of the Irish and the British: "The term that Swift uses to describe the oppression in both Ireland and Houyhnhnmland is 'slavery'; this is not an accidental word choice, for Swift was well aware of the complicated moral and philosophical questions raised by the emotional designation 'slavery.' The misery of the Irish gaelic in the early eighteenth century shocked Swift and all others who witnessed it; the hopeless passivity of the people in this desolate state made it seem as if both the minds and bodies of the Irish were enslaved."[22] Kelly goes on to write: "Throughout the Irish gaelic tracts and poems, Swift continually vacillates every bit to whether the Irish are servile because of some defect inside their graphic symbol or whether their sordid condition is the result of a calculated policy from without to reduce them to brutishness. Although no 1 has done so, similar questions could exist asked nearly the Yahoos, who are slaves to the Houyhnhnms." However, Kelly does not suggest a wholesale equivalence between Irish and Yahoos, which would be reductive and omit the various other layers of satire at work in this section.

Reception [edit]

The book was very popular upon release and was commonly discussed within social circles.[23] Public reception widely varied, with the book receiving an initially enthusiastic reaction with readers praising its satire, and some reporting that the satire's cleverness sounded like a realistic business relationship of a man's travels.[24] James Beattie commended Swift's work for its "truth" regarding the narration and claims that "the statesman, the philosopher, and the critick, will admire his keenness of satire, energy of description, and vivacity of linguistic communication", noting that even children tin enjoy the novel.[25] As popularity increased, critics came to appreciate the deeper aspects of Gulliver's Travels. It became known for its insightful take on morality, expanding its reputation beyond just humorous satire.[24]

Despite its initial positive reception, the book faced backlash. One of the showtime critics of the book, referred to equally Lord Bolingbroke, criticized Swift for his overt apply of misanthropy.[24] Other negative responses to the volume also looked towards its portrayal of humanity, which was considered inaccurate. Swifts'due south peers rejected the book on claims that its themes of misanthropy were harmful and offensive. They criticized its satire for exceeding what was deemed acceptable and appropriate, including the Houyhnhnms and Yahoos's similarities to humans.[25] There was also controversy surrounding the political allegories. Readers enjoyed the political references, finding them humorous. Nonetheless, members of the Whig party were offended, believing that Swift mocked their politics.[24]

British novelist and journalist William Makepeace Thackeray described Swift'south work as "cursing", citing its critical view of flesh as ludicrous and overly harsh. He concludes his critique by remarking that he cannot understand the origins of Swift's critiques on humanity.[25]

Cultural influences [edit]

The term Fiddling has entered many languages as an adjective meaning "modest and fragile". There is a brand of small cigar chosen Lilliput, and a series of collectable model houses known every bit "Lilliput Lane". The smallest light bulb plumbing equipment (5 mm diameter) in the Edison screw series is chosen the "Lilliput Edison screw". In Dutch and Czech, the words Lilliputter and lilipután, respectively, are used for adults shorter than ane.30 meters. Conversely, Brobdingnagian appears in the Oxford English Dictionary as a synonym for very large or gigantic.

In similar vein, the term yahoo is often encountered as a synonym for ruffian or thug. In the Oxford English Dictionary information technology is defined as "a rude, noisy, or fierce person" and its origins attributed to Swift'due south Gulliver's Travels.[26]

In the discipline of computer architecture, the terms big-endian and picayune-endian are used to depict ii possible ways of laying out bytes in memory. The terms derive from one of the satirical conflicts in the book, in which two religious sects of Lilliputians are divided between those who crack open their soft-boiled eggs from the piffling end, the "Little-endians", and those who use the big end, the "Large-endians".

It has been pointed out that the long and vicious war which started afterwards a disagreement about which was the all-time end to intermission an egg is an example of the narcissism of small-scale differences, a term Sigmund Freud coined in the early 1900s.[27]

In other works [edit]

Many sequels followed the initial publishing of the Travels. The earliest of these was the anonymously authored Memoirs of the Courtroom of Lilliput,[28] published 1727, which expands the account of Gulliver'south stays in Lilliput and Blefuscu by adding several gossipy anecdotes almost scandalous episodes at the Lilliputian court. Abbé Pierre Desfontaines, the kickoff French translator of Swift's story, wrote a sequel, Le Nouveau Gulliver ou Voyages de Jean Gulliver, fils du capitaine Lemuel Gulliver (The New Gulliver, or the travels of John Gulliver, son of Captain Lemuel Gulliver), published in 1730.[29] Gulliver'south son has various fantastic, satirical adventures.

Adaptations [edit]

Comic book cover by Lilian Chesney

Motion-picture show [edit]

- Gulliver'south Travels Among the Lilliputians and the Giants, a 1902 French silent film directed past Georges Méliès

- Gulliver's Travels, a 1924 Austrian silent take chances motion-picture show

- The New Gulliver, a 1935 Soviet motion-picture show

- Gulliver's Travels, a 1939 American blithe film

- The three Worlds of Gulliver, a 1960 American movie loosely based on the novel, also known as Gulliver's Travels

- Gulliver's Travels Across the Moon, a 1965 Japanese animated film featuring Gulliver as a character

- Gulliver's Travels, a 1977 British-Belgian film starring Richard Harris

- Gulliver'southward Travels, a 1996 blithe film by Golden Films

- Jajantaram Mamantaram, a 2003 Indian film starring Jaaved Jaaferi

- Gulliver'southward Travels, a 2010 American film starring Jack Black

Television [edit]

- Gulliver's Travels, a 1979 TV special produced by Hanna-Barbera

- Saban'due south Gulliver's Travels, a 1992 French blithe Goggle box series

- Gulliver'southward Travels, a 1996 American Television miniseries starring Ted Danson

Radio [edit]

- Gulliver'due south Travels, a 1999 radio adaptation in the Radio Tales series

- Brian Gulliver's Travels, a satirical radio series starring Neil Pearson

Bibliography [edit]

Editions [edit]

The standard edition of Jonathan Swift's prose works every bit of 2005[update] is the Prose Writings in 16 volumes, edited by Herbert Davis et al.[30]

- Swift, Jonathan Gulliver's Travels (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2008) ISBN 978-0141439495. Edited with an introduction and notes by Robert DeMaria Jr. The copytext is based on the 1726 edition with emendations and additions from after texts and manuscripts.

- Swift, Jonathan Gulliver's Travels (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005) ISBN 978-0192805348. Edited with an introduction by Claude Rawson and notes by Ian Higgins. Essentially based on the aforementioned text as the Essential Writings listed below with expanded notes and an introduction, although it lacks the selection of criticism.

- Swift, Jonathan The Essential Writings of Jonathan Swift (New York: West.Due west. Norton, 2009) ISBN 978-0393930658. Edited with an introduction by Claude Rawson and notes by Ian Higgins. This championship contains the major works of Swift in full, including Gulliver's Travels, A Small Proposal, A Tale of a Tub, Directions to Servants and many other poetic and prose works. Also included is a pick of contextual material, and criticism from Orwell to Rawson. The text of GT is taken from Faulkner'southward 1735 edition.

- Swift, Jonathan Gulliver'southward Travels (New York: Westward.West. Norton, 2001) ISBN 0393957241. Edited by Albert J. Rivero. Based on the 1726 text, with some adopted emendations from subsequently corrections and editions. Also includes a selection of contextual textile, letters, and criticism.

Meet also [edit]

- Aeneid

- List of literary cycles

- Odyssey

- Sinbad the Sailor

- Sunpadh

- The Voyage of Bran

References [edit]

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (2003). DeMaria, Robert J (ed.). Gulliver's Travels. Penguin. p. xi.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (2009). Rawson, Claude (ed.). Gulliver'due south Travels. W. West. Norton. p. 875. ISBN978-0-393-93065-8.

- ^ Gay, John. "Letter of the alphabet to Jonathan Swift". Communion. Communion Arts Periodical. Retrieved 9 Jan 2019.

- ^ "The 100 best novels written in English: the total list". TheGuardian.com. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Example, Arthur E. (1945). "The Geography and Chronology of Gulliver'southward Travels". Four Essays on Gulliver's Travels. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Ehrenpreis, Irvin (December 1957). "The Origins of Gulliver's Travels". PMLA. 72 (5): 880–899. doi:10.2307/460368. JSTOR 460368 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Clive Probyn, Swift, Jonathan (1667–1745), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2004)

- ^ Daily Periodical 28 October 1726, "This twenty-four hours is published".

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (1980). Isaac Asimov (ed.). The Annotated Gulliver'southward Travels. New York: Clarkson N Potter Inc. p. 160. ISBN0-517-539497.

- ^ Allan Blossom (1990). Giants and Dwarfs: An Outline of Gulliver's Travels. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 47–51.

- ^ a b Swift, Jonathan (1994). Gulliver's travels : consummate, authoritative text with biographical and historical contexts, critical history, and essays from five contemporary critical perspectives. Fox, Christopher. Boston. ISBN978-0312066659. OCLC 31794911.

- ^ Rogers, Katharine Chiliad. (1959). "'My Female Friends': The Misogyny of Jonathan Swift". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 1 (3): 366–79. JSTOR 40753638.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (1995). Gulliver's travels : complete, authoritative text with biographical and historical contexts, critical history, and essays from five contemporary critical perspectives. Fox, Christopher. Boston. ISBN0-312-10284-4. OCLC 31794911.

- ^ Armintor, Deborah Needleman (2007). "The Sexual Politics of Microscopy in Brobdingnag". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 47 (three): 619–40. doi:10.1353/sel.2007.0022. JSTOR 4625129. S2CID 154298114.

- ^ a b c Case, Arthur Due east. "From 'The Significance of Gulliver's Travels.'" A Casebook on Gulliver Among the Houyhnhnms, edited by Milton P. Foster, Thomas Y. Crowell Visitor, 1961, pp. 139–47.

- ^ a b c d Crane, R.S. "The Houyhnhnms, the Yahoos, and the History of Ideas". Twentieth Century Interpretations of Gulliver'southward Travels: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Frank Brady, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1968, pp. lxxx–88.

- ^ a b c d Stone, Edward. "Swift and the Horses: Misanthropy or Comedy?" A Casebook on Gulliver Amid the Houyhnhnms, edited by Milton P. Foster, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1961, pp. 180–92.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (1726). Gulliver'south Travels. p. 490. ISBN978-0-393-93065-8.

- ^ James Clifford, "Gulliver's Fourth Voyage: 'hard' and 'soft' Schools of Estimation". Quick Springs of Sense: Studies in the Eighteenth Century. Ed. Larry Champion. Athens: U of Georgia Press, 1974. 33–49

- ^ Harth, Phillip (May 1976). "The Trouble of Political Allegory in "Gulliver's Travels"". Modernistic Philology. 73 (4, Part ii): S40–S47. doi:10.1086/390691. ISSN 0026-8232. S2CID 154047160.

- ^ a b TREADWELL, J. G. (1975). "Jonathan Swift: The Satirist as Projector". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 17 (2): 439–460. ISSN 0040-4691. JSTOR 40754389.

- ^ Kelly, Ann Cline (October 1976). "Swift's Explorations of Slavery in Houyhnhnmland and Ireland". PMLA/Publications of the Modern Linguistic communication Clan of America. 91 (five): 846–855. doi:10.2307/461560. ISSN 0030-8129. JSTOR 461560.

- ^ Wiener, Gary, editor. "The Enthusiastic Reception of Gulliver's Travels". Readings on Gulliver'due south Travels, Greenhaven Press, 2000, pp. 57–65.

- ^ a b c d Gerace, Mary. "The Reputation of 'Gulliver'southward Travels' in the Eighteenth Century". University of Windsor, 1967.

- ^ a b c Lund, Roger D. Johnathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels: A Routledge Study Guide. Routledge, 2006.

- ^ "yahoo – definition of yahoo in English". Oxford Dictionaries.

- ^ Fintan O'Toole Pathological narcissism stymies Fianna Fáil support for Fine Gael, The Irish Times, March 16, 2016

- ^ "Memoirs of the Courtroom of Lilliput". J. Roberts. 1727.

- ^ fifty'abbé), Desfontaines (Pierre-François Guyot, M.; Swift, Jonathan (1730). "Le nouveau Gulliver: ou, Voyage de Jean Gulliver, fils du capitaine Gulliver". La veuve Clouzier.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (2005). Rawson, Claude; Higgins, Ian (eds.). Gulliver's Travels (New ed.). Oxford. p. xlviii.

External links [edit]

- Digital editions

- Gulliver'south Travels at Standard Ebooks

- Gulliver's Travels at Project Gutenberg (1727 ed.)

- Gulliver'southward Travels at Projection Gutenberg (1900 ed.; with illustrations)

-

Gulliver's Travels public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Gulliver's Travels public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Gulliver's Travels at the Cyberspace Annal

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulliver%27s_Travels

0 Response to "in gullivers travels, what are the lilliputians quarreling about that leads to war?"

Post a Comment