what are the repercussions for physicians to follow up on screening mammograms

- Inquiry article

- Open Access

- Published:

Delayed or failure to follow-upwards abnormal breast cancer screening mammograms in primary care: a systematic review

BMC Cancer volume 21, Article number:373 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Successful breast cancer screening relies on timely follow-upwardly of abnormal mammograms. Delayed or failure to follow-upwards abnormal mammograms undermines the potential benefits of screening and is associated with poorer outcomes. However, a comprehensive review of inadequate follow-up of abnormal mammograms in master intendance has not previously been reported in the literature. This review could place modifiable factors that influence follow-up, which if addressed, may lead to improved follow-upward and patient outcomes.

Methods

A systematic literature review to make up one's mind the extent of inadequate follow-up of aberrant screening mammograms in main care and place factors impacting on follow-up was conducted. Relevant studies published between i January, 1990 and 29 October, 2020 were identified by searching MEDLINE®, Embase, CINAHL® and Cochrane Library, including reference and citation checking. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklists were used to assess the risk of bias of included studies according to written report design.

Results

Xviii publications reporting on 17 studies met inclusion criteria; 16 quantitative and ii qualitative studies. All studies were conducted in the United States, except ane report from the Netherlands. Failure to follow-upward abnormal screening mammograms within 3 and at 6 months ranged from seven.two–33% and 27.3–71.6%, respectively. Women of ethnic minority and lower teaching attainment were more likely to have inadequate follow-up. Factors influencing follow-up included physician-patient miscommunication, information overload created by automated alerts, the absence of adequate retrieval systems to access patient's results and a lack of coordination of patient records. Logistical barriers to follow-up included inconvenient clinic hours and inconsistent primary intendance providers. Patient navigation and case management with increased patient education and counselling by physicians was demonstrated to improve follow-upward.

Conclusions

Follow-upward of abnormal mammograms in primary intendance is suboptimal. Withal, interventions addressing amendable factors that negatively touch on on follow-upwardly take the potential to meliorate follow-up, particularly for populations of women at run a risk of inadequate follow-upwardly.

Background

Breast cancer is the most unremarkably diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of cancer-related death amidst women worldwide [1]. The standard of care for breast cancer screening is digital mammography, which is associated with a twenty% reduction in breast cancer-related mortality in women at boilerplate take a chance of breast cancer [two, 3]. Mammographic screening relies on the follow-up of abnormal (potentially clinically pregnant) mammograms in a timely manner. Delays in follow-up may compromise the prognostic benefits of screening, [4, 5] and atomic number 82 to increased emotional distress and anxiety [6].

Breast screening guidelines in the United States (Usa) and Europe recommend women receive notification of abnormal mammogram results within v days of the master care provider's (PCP's) receipt of results [7, 8]. In Australia and the Netherlands, clinical guidelines recommend women should receive mammogram results within 28 days and 14 days of screening, respectively [9, 10]. To guide follow-up, American Higher of Radiology (ACR) Breast Imaging Reporting and Information Organization® (BIRADS®) is used to classify mammograms, with highly suggestive of malignancy (BIRADS®-5), suspicious malignancy (BIRADS®-4) or indeterminant (BIRADS®-0) mammograms recommended immediate (inside 3 months) follow-upward and likely benign (BIRADS®-3) mammograms recommended short term (3–half dozen months) follow-upwards [7, 11].

In many healthcare systems, specially in the US, primary care providers (PCPs) play a critical role in promoting and encouraging patient participation in preventative health services, including mammography screening, every bit well as organising these preventative services [12]. In particular, PCPs take an important influence on providing unlike modalities of chest cancer screening across women of all ages, either every bit organised (population-based) mammography screening usually for women over 50 years or non-organised patient or PCP-driven (opportunistic) screening [13]. Moreover, PCPs act as "gate-keepers" to secondary intendance for the diagnostic assessment of abnormal mammograms to ensure timely follow-upwardly to diagnostic resolution, [14] but are as well responsible for informing patients of abnormal mammogram results, potential impacts on patients' wellness status and recommended follow-upward investigation and critically, timely intervention [11, 15]. Despite this, several studies report that follow-upwards of abnormal mammogram results in primary care is suboptimal, with delayed follow-up associated with poorer patient morbidity and bloodshed outcomes [4, v]. The extent of inadequate follow-up in primary care and factors influencing follow-upwards has not been well-studied, withal, there is evidence to suggest delayed follow-upwardly is due to health organization-, PCP- and patient-related barriers [16,17,xviii,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Despite the vital role PCPs play in breast screening (both organised and non-organised), specially in the US, the effectiveness of follow-up after aberrant mammography in master intendance has not been well-studied. This nowadays study aimed to systematically review the bear witness related to inadequate follow-upward of abnormal screening mammograms amidst women in master care and identify factors influencing the follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms in primary care. Increased understanding of the extent of inadequate follow-up and barriers to follow-upward will enable primary care-specific targeted interventions addressing barriers to inadequate follow-up to be devised, which in turn may improve follow-up and ultimately, patient outcomes, particularly for women identified equally existence at the highest take a chance of inadequate follow-up.

Methods

A systematic review of relevant studies was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria [28]. This review was registered in PROSPERO (Registration ID: CRD42019139517).

The ACR BIRADS® reporting tool was used to define aberrant or clinically pregnant mammograms (BIRADS®-0, BIRADS®-3, BIRADS®-4 or BIRADS®-5) [7].

Search strategy

Medical Field of study Headings (MeSH) terms were used to search 4 databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE via Ovid, the Cochrane Central Annals of Controlled Trials, and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The search strategy was an intersection of MeSH terms referring to "family practice" or "primary intendance", "filibuster"/"follow-up"/"errors" and "screening"/"cancer screening" tests for breast, colorectal, gynaecological, prostate, lung, liver and pare cancer to capture all relevant articles related to inadequate follow-upwardly of aberrant tests results for these cancers to enable a series of systematic reviews to be performed examining inadequate follow-up for each corresponding cancer. Studies pertaining to inadequate follow-up (failure to follow-upwardly, delayed follow-upward or inappropriate follow-up) of aberrant screening mammograms in principal/community/ambulatory/family unit practice settings were specifically selected for this review via relevant abstracts identified and independently reviewed by 2 co-authors (P.N., J.C.R.). The full electronic search strategy is available in Supplementary Table 1.

Full text articles that fulfilled the study criteria were identified by two contained reviewers (J.C.R., Due east.F.G.N.), and included transmission reference and citation checking to identify relevant studies non found from the search. Studies were included if they specifically examined inadequate follow-upward after abnormal screening mammogram. Studies that exclusively examined appropriate/timely follow-up every bit the outcome were excluded. This determination was made to avoid making the potentially incorrect assumption that women that did not have adequate follow-up equated to inadequate follow-up as these women may accept accessed care elsewhere.

Data abstraction

Data from full text manufactures were independently abstracted and evaluated by two co-authors (J.C.R. and E.F.G.N.). Any discrepancies between reviewers were discussed and resolved by consultation with a third reviewer (J.D.E.). A standardized data extraction form was used to confirm written report eligibility, evaluate study and participant characteristics and extract data from included studies [29].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted of studies:

-

published betwixt 1 January, 1990 and 29 October, 2020.

-

conducted in primary care or a Usa community-based setting that included family unit practice, internal medicine or obstetrics/gynaecology services in public or individual facilities provided ≥80% was in primary care

-

examined inadequate abnormal mammogram follow-up of breast cancer screening mammograms (not diagnostic mammograms)

Studies were excluded if they:

-

exclusively examined timely follow-upwardly of abnormal mammograms just did non mensurate inadequate follow-upward

-

included women with a current or prior history of breast cancer

-

examined follow-up of clinical symptoms and mammograms collectively

-

did not delineate abnormal mammogram follow-up in the context of examining multiple cancers collectively

-

examined follow-up of diagnostic mammograms

-

were non in English

-

were unpublished work, academic theses or briefing abstracts

-

were example studies, reviews, protocols or editorials

-

were studies involving men with breast cancer

-

were studies that exclusively examined inadequate follow-up resulting in malpractice claims due to the high selection bias of report participants

Cess of risk of bias

Studies were assessed for take chances of bias by two reviewers (East.F.Grand.N. and J.C.R.) using the Joanna Briggs Found (JBI) Critical Appraisement Checklists, [30] using advisable checklist for study blazon:

-

cross-sectional

-

cohort

-

randomised control trial (RCT)

-

qualitative research

The JBI tool comprises 8–12 questions, with possible answers "yes", "no", "unclear" or "not applicable" depending on written report type. To define the quality of studies, questions assessed as low take chances of bias were divided by the full number of questions to decide a percentage score. Studies were classified as low (> lxxx%), moderate (60–80%) and high risk (< threescore%) of bias prior to commencing adventure appraisals [31, 32]. Studies were not excluded based on their risk of bias to ensure transparency and completeness of reporting findings from all studies identified equally relevant for the review as recommended past Shea et al. [33].

The percent of women with aberrant mammograms that had inadequate follow-up in each study was extracted. We reported factors positively or negatively associated with follow-up (inadequate or adequate) to provide a comprehensive picture of all barriers and facilitators of follow-upward. Principal summary measures are described every bit reported in each eligible study.

A meta-analysis was non performed due to the heterogeneity of the data in the included studies, instead a narrative review of results in the eligible studies was conducted.

Results

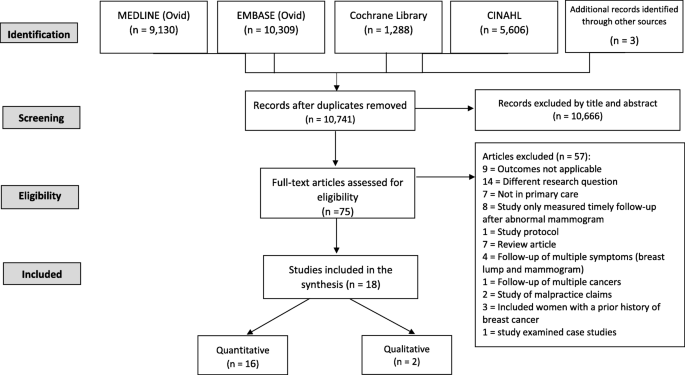

The search strategy identified 10,741 titles, of which 75 full text manufactures were reviewed for eligibility (Fig. one). Eighteen articles reporting on 17 individual studies were included in the systematic review.

PRISMA flow diagram of inclusion of studies

Characteristics of included studies chronologically ordered by publication appointment are outlined in Tabular array 1. Studies comprised i randomised controlled trial (RCT), [34] 11 cohort, [xvi, xviii, xix, 21, 22, 24, 25, 35,36,37,38] two cross-sectional, [23, 27], two qualitative studies, [39, xl] and two mixed method studies (cross-sectional and qualitative, [17] and cohort and qualitative) [26]. All studies were US-based, except one accomplice written report from the netherlands [26].

JBI run a risk of bias assessments identified 10 articles at low adventure of bias, seven at moderate risk and one at high risk (Table 2, Supplementary Table two).

Study findings are summarised in Table 2. The definition of inadequate follow-upward following abnormal mammogram varied across studies and included:

-

Failure to attend scheduled/recommended follow-up, [18, 21, 23, 25, 26, 41] or whatsoever follow-upwards within a specified time, [19, 22, 27, 38,39,forty]

-

Failure to undergo consummate follow-upwards to diagnostic resolution, [sixteen, 17, 34, 35]

-

Failure of PCP to inform patient of abnormal mammogram consequence, [36] and

-

PCP failed to admit follow-up alphabetic character, was not enlightened of result or had no follow-upwardly program [37].

Measures of follow-up subsequently abnormal mammogram included specialist referrals and/or attendance, diagnostic imaging and/or fine needle biopsy, open surgical biopsy or undergo consummate follow-upwards to diagnostic resolution equally per recommended guidelines [42, 43].

Rates of inadequate follow-upwards

Rates of inadequate aberrant mammogram follow-up are presented in Table 2. Studies are ordered chronologically by publication date to reflect any reduction in inadequate abnormal mammogram follow-up that has occurred over time, particularly delays in the complete follow-upwards to diagnostic resolution, due to the implementation of avant-garde technology that has increased diagnostic accurateness and reduced fake positives [44]. These innovations include the replacement of screen-pic mammography with full-field digital mammography after 2009 and the introduction of new diagnostic modalities including 3D ultrasonography, advanced MRI techniques, and core biopsies to replace fine needle aspiration.

Ten studies examinedfailure to attend any follow-up after an abnormal breast screen result [19, 21, 23,24,25,26,27, 37]. Ii of these studies reported rates of seven.2–33% non-attendance inside a 3 month follow-up flow, [21, 25] and four studies reported rates of 27.3–71.6% non-attendance to 6-monthfollow-up [23,24,25,26]. Yabroff et al. and Nguyen et al. found 8.6%, [27] and 11.3%, [nineteen] of women, respectively, had not attended follow-up within one year. One study described a "fail-condom" organization where only 1% of women with abnormal mammogram results failed to nourish follow-up [37].

Two studies examined failure to undergo complete diagnostic follow-up. The starting time, a retrospective analysis of clinical records, found 68.4% of women had incomplete follow-up inside sixty days of an abnormal mammogram and 34% after xi months [35]. The second was an RCT: The SAFe (Screening Adherence Follow-up) trial, where the Rubber intervention comprised patient navigation/case management intervention with increased education and counselling that aimed to reduce rates of incomplete diagnostic follow-upwards. Inadequate follow-up betwixt control and intervention groups was 43 and 23% (p = 0.01), respectively, subsequently 60 days, and 34 and 10% (p < 0.001), respectively, after 8 months [34].

2 qualitative studies did not study rates of inadequate follow-up but explored barriers and facilitators to abnormal mammogram follow-up [39, twoscore].

Factors contributing to abnormal mammogram follow-upwardly

Factors influencing follow-up of abnormal mammograms were classified into health system-, PCP- or patient-related factors (Table 2).

Wellness system-related factors

Electronic wellness record (EHR)

2 studies examined the use of EHRs to manage the follow-upwards of abnormal mammograms with comparable results [36, 39]. Qualitative interviewing of 37 PCPs constitute current health information technology that supported the notification of aberrant cancer screening results, including mammograms, created information overload in PCPs' EHR inbox and contributed to inadequate follow-up [39]. Similarly, Casalino et al. found EHRs that included both test results and patient progress notes were associated with inadequate follow-upward compared with having no EHR for a number of abnormal test results examined, including abnormal mammograms [Odds Ratio (OR) = two.37; P = 0.007) [36].

Coordindation between healthcare systems

Smith et al. found PCPs perceived that a lack of coordination across distributed healthcare services, including insufficient information management across organizations and ambiguity about their responsibility in follow-up, contributed to inadequate follow-up [39].

Reminders

2 studies provided evidence to support the effectiveness of reminders to improve follow-up [26, 37]. In the commencement report, abnormal mammograms were flagged and internally tracked by the radiology department who were responsible for notifying patients of abnormal results by letter and arranging follow-upwardly tests [37]. In the effect the radiology section could not contact the patient, the referring clinician was contacted for assistance. This proved to be a highly constructive method for following up women, with simply 1% of women not followed up, and at 3 months only vii.7% of PCPs were unaware of the abnormal mammogram. In the 2d study, radiologists sent a reminder to PCPs if women were overdue for their 6 monthly follow upwards and resulted in a reduction of non-attendance to follow-up from 71.6 to 32.5% [26].

Retrieval of patient information

The study by Duijm et al. sent a questionnaire with reminders to PCPs to explore why the patients had not attended follow-up [26]. Failure to follow-up patients was reportedly clinician driven rather than patient driven, with greater than 90% of PCPs perceiving the absence of adequate retrieval systems to access patient's results was the chief reason for inadequate follow-up (both before and after PCPs received a 6-monthfollow-up reminder).

Patient navigation/example management

In the Rubber RCT, women in the intervention group received an individualised nurse-delivered patient navigation/case management intervention that included telephone-based health education and counselling based on their risk, reminders and referral to community resource. The results supported the potential of patient navigation to ameliorate abnormal mammogram follow-upwards; women with BIRAD®-4/− five mammograms enrolled in SAFe were 2.5 times more than probable to have consummate follow-up within lx days than women in usual care (95% CI one.36–four.59), with women with BIRAD®-iii mammograms enrolled in SAFe 4.5 times more likely to complete follow-upwards within viii months compared with women in usual care (95% CI 2.08–nine.64; P < 0.001) [34].

Logistical barriers to access follow-up

Qualitative interview of women who had inadequate follow-up identified inconvenient appointment hours, [17, 40] lengthy dispensary waiting times, [17, forty] loss of income, [17] costs, [17] transportation issues, [17, 40] childcare problems, [17, 40] and follow-up in unfamiliar settings every bit logistical barriers to follow-up [40]. Duijm et al. constitute around one-quarter of women failed to have follow-upwardly because having some other mammogram was inconvenient [26].

In dissimilarity, quantitative studies found no association between clinic waiting times [problematic vs non-problematic; (Adjusted Risk Ratio) ARR = i.one; 95%CI 0.5–2.8)], [xviii] transportation problems (large/some vs fiddling/non; ARR = 3.1; 95%CI 0.five–18.3), [18] or costs (referral vs no referral; OR = 0.75; 95%CI 0.44–1.29), [27] and follow-up only living less than lxx miles to follow-upward care increased the likelihood of follow-up (P < 0.05) [16]. Difficulty obtaining a medical engagement increased the likelihood of non-omnipresence within 3 months past iv.i-fold (95%CI one.5–11.3) [xviii]..

2 smaller studies examined the association betwixt usual intendance and follow-up with conflicting findings: Jones et al. found an association between failure to attend follow-upwards and non having a usual PCP [Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 4.29; 95%CI 1.48–12.42)], [21] whereas in the quantitative component of the Rojas et al. written report, regular versus irregular care was not associated with follow-upwardly (P = 0.28) [17].

Radiology report comments

Two of three studies found comments on radiology reports influenced follow-upward (Table 2) [21, 35]. Burack et al. institute inclusion of a specific follow-upward recommendation by the radiologist in the index mammogram report compared with no recommendation was associated with increased follow-up within 60 days (aOR = iii.55; 95%CI 1.14–11.04) and at least eleven months subsequently the index mammogram (aOR = 4.58; 95%CI ane.54–13.62) [35]. Similarly, non-attendance was higher when short-termfollow-up was recommended compared with immediate follow-up. MCarthy et al. (1996a) found 7.2% of women had no follow-upwards testing when immediate follow-up was recommended whereas 36.8% of women had no follow-upwardly testing when short-termfollow-up was recommended [25]. Jones et al. plant non-attendance to iii–half dozen months follow-up for BIRADS®-3 mammograms was 47.vi%, whereas not-attendance within a 3-monthfollow-up period for BIRADS®-0 and BIRADS®-4/− 5 was 25.five and 33%, respectively [21]. Conversely, Grossman et al. constitute no difference in non-omnipresence to follow-upwardly for BIRADS®-0/− iii vs BIRADS®-four/− 5, [37] but this is not surprising given immediate follow-upwardly is recommended for BIRADS®-0 and BIRADS®-4/5 [7, 11, 21]. Wernli et al. constitute extremely dense compared with 'almost entirely fat' mammograms were less likely to have delayed follow-up within 7 days compared with at least 7 days (OR = 0.82; 95%CI 0.69–0.96) [22].

PCP-related factors

Advice to patients

Two studies had conflicted findings in regards to the effectiveness of PCP-patient advice and adequate fourth dimension to follow-up [21, 24]. In 1 written report, patients who had an understanding of their aberrant mammogram results and of the need for follow-up were 3.86 times more than likely to attend follow-upwards (95%CI 1.50–nine.96; P = 0.006) [24]. In contrast, a small report by Jones et al. found no association betwixt inadequate advice of results and delayed follow-up (aOR = 0.threescore; 95%CI 0.20–1.83) [21].

Other studies plant PCPs had not informed some women of abnormal mammogram results or of the demand for follow-up. Casalino et al. found that 5.3% of women had not been informed of their aberrant mammogram within xc days, [36] and in women that failed to attend six-monthfollow-upwards, McCarthy et al. found 13% were not notified of their aberrant mammogram [25]. In women who were not-compliant to complete follow-up, 35% were non informed of the demand for follow-upward compared with 0% of women who were compliant (P = 0.008) [17].

Qualitative interviews of 33 low-incomeethnically-various women with inadequate follow-upwards found all women were dissatisfied with the lack of information on abnormal mammogram results and recommended follow-upward provided by their PCP and some experienced disrespectful behaviour, mistreatment, lack of courtesy, privacy and/or trust in conveying exam results and suspicion regarding financial motives of recommending follow-upward [40]. Comparatively, women that had adequate follow-upward (n = 31) cited that communication efforts by PCPs and clinic staff, such as reminder phone calls and letters, were fundamental to their compliance with follow-up [xl].

PCPs' expertise

Grossman et al. found PCPs who had less clinical experience were less likely to be enlightened of abnormal mammogram results (aOR = 0.92; 95%CI 0.88–0.97; P < 0.05) and less likely to have a follow-up plan (aOR = 0.93; 95%CI 0.87–0.99; P < 0.05). However, professional status [Resident or fellow vs attending doc (aOR = 1.ten; 95%CI 0.21–5.69)] or number of clinical sessions per week [sessions/week: < 2, 2–2.nine, 3–3.ix, 4+ (aOR = 0.64; 95%CI 0.12–3.29)], did not impact on follow-upwardly.) [37]. Women that had PCPs with documented evidence of follow-up plans were 2.8 times more probable to receive adequate follow-up (95%CI 1.11–six.98; P = 0.029) [24].

Patient-related factors

Patient-related factors were classified into sociodemographic, psychological or clinical.

Sociodemographic factors

Age

5 studies constitute older women were more than probable to have adequate follow-upwardly (50+ years, [24] 65+ years, [23, 27] and 70+ years), [19, 22] yet, ii studies had alien findings, [19, 35] and 2 studies plant no clan between historic period and acceptable follow-up [17, xviii, 25].

Ethnicity

Jones et al. and Nguyen et al. found African-American and Asian women were more likely to have inadequate follow-upwardly [19, 21]. However, seven studies found no association between ethnicity/race (African-American, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islanders, White or other) and follow-upwards [xvi,17,18, 22,23,24,25, 37].

Income

Three studies found low household income did not influence follow-up (<$USD20K vs ≥ $USD20K, [eighteen, 35] and < $USD10K vs > $USD15K or $USD10K-$USD15K vs > $USD15K), [sixteen] whereas McCarthy et al. found income (≤$USD20K vs > USD$20 K) was associated with not-attendance to six-monthfollow-upwardly (ARR = two.one; 95%CI 1.ii–iii.ix). Nonetheless, this analysis adapted for all variables, [25] and subsequent analyses only adjusting for relevant variables found this association was no longer pregnant [18].

Health insurance

7 studies examined the bear upon of health insurance status (public, [27] private/military, [17, 27] Medicare, [17, 37] Medicaid, [17, 35, 37] managed care, [24] "insurance with full mammogram coverage", [21] commercial, [37] or non specified) [16] on follow-up. Of these, merely managed intendance was associated with increased likelihood to attend follow-up (aOR = 3.54; 95%CI one.17–ten.66; P = 0.026) [24]..

Education

Ii of six studies found lower educational attainment was associated with inadequate follow-upwardly [19, 27]. Yabroff et al. and Nguyen et al. found women with formal education below high school were less likely to attend follow-up than college graduates or higher (OR = 0.56; 95%CI 0.32–0.98, [27] and Adjusted Take chances Ratio (aHR) = 0.75; 95%CI 0.72–0.78, [19] respectively). Loftier school graduates were also less likely to attend follow-upward than college graduates or higher (aHR = 0.86; 95%CI 0.83–0.89) [xix]..

Marital status

3 private studies establish no association between marital status and follow-up [16, xviii, 21].

Employment/occupation

Ii studies found no association between employment status at fourth dimension of mammogram and follow-up [18, 21].

Psychological factors

Qualitative interview of women with inadequate follow-upward identified psychological barriers to follow-up, including fatalism, [17] pain/embarrassment, [17, 26] and fear of breast cancer, [40] of losing a chest, [17] and of radiation [26]. While interviews are beneficial in helping provide an understanding of women's interpretations of their own experiences, quantitative analyses found fear of a chest cancer diagnosis, [17, eighteen, 24] perceived benefit of mammograms, [18] and mammogram pain/discomfort were not associated with inadequate follow-up [24]. However, the small study by Jones et al. found pain was a significant predictor of inadequate follow-up, with women experiencing painful mammograms 2.8 times (95%CI ane.21–6.47) less likely to attend follow-upwardly compared with women who experienced little/no pain during mammograms [21].

Allen et al. found facilitators of adequate follow upward included women's confidence to advocate for themselves and have responsibility for their self-care [40].

Clinical factors

Health status

Health condition did non influence follow-up. While Yabroff et al. found self-reported health was associated with non-omnipresence to follow-up ("fair/poor/missing" vs "excellent/very skilful", OR = 0.sixty; 95%CI 0.37–0.97), lack of data on missing data prevented conclusive inferences [27]. Burack et al. likewise establish frequency of primary intendance visits in the previous year was not associated with complete follow-up [35].

Family unit history of breast cancer

Two of five studies found a family history of chest cancer was associated with adequate follow-up [17, xix, 22, 24, 27].

Yabroff et al. found women with a loftier risk family history were 1.65 times (95%CI 1.04–2.62) more likely to attend follow-upward than women with depression risk, but medium risk family unit history vs no history was not significantly associated with follow-up (OR = 0.84; 95%CI 0.53–1.33) [27]. Likewise, Nguyen et al. institute a family history of breast cancer was associated with attendance at follow-up (aHR = 1.05; 95%CI 1.02–one.07) [19]. Iii studies found no association between breast cancer family history and follow-up [17, 22, 24].

Chest symptoms

3 of four studies found the presence of breast symptoms (due east.m. a lump) that occurred incidentally at the time of the screening mammogram influenced follow-upwards [22, 26, 35, 38]. Schootman et al. found the presence of a lump vs other/no lump was associated with attendance to follow-upward (aRR = 2.08; 95%CI 1.18–iii.64) [38]. Wernli et al. found women with breast symptoms were less likely to accept delayed follow-up within 7 days (aOR = 0.47; 95%CI 0.39–0.56) [22]. Conversely, Burack et al. found no association between breast symptoms and follow-upwards [35]. Qualitative interview of women with inadequate follow-up by Duijm et al. establish 43.8% of women attributed "no breast complaints" for their failure to attend follow-up [26].

A history of mammograms and in detail a history of fewer mammograms (i–2 vs 3–4) was associated with non-attendance to 6-monthfollow-up (aRR = iv.0; 95%CI i.6–ten.4, [eighteen] and aRR = ane.vi; 95%CI 1.1–2.iii, respectively) [25]. However, Rojas et al. [17] and Poon et al. [24] found no association between prior mammogram history (or prior abnormal mammogram history) and follow-up.

Discussion

Screening mammography is an constructive strategy for the early detection of breast cancer and is associated with reduced mortality [ii, 45]. However, delays in the follow-upwards of abnormal mammogram results may compromise the prognostic benefits of screening [4, five]. This systematic review of 18 articles (reporting on 17 private studies) examining inadequate follow-up of abnormal mammograms in master care identified suboptimal follow-up across all included studies, except one written report with a newspaper-based "neglect-safe" organisation for follow-upward where patients were tracked and followed upwards past the radiology department and the clinician only became involved when the patient could non be contacted [37].

Failure to attend recommended 6-month scheduled follow-up for lower risk mammograms (BIRADS®-iii) (the almost frequently-examined mensurate of inadequate follow-up) was 27.3, 35.7, 36.8% in three US-based studies, [23, 25, 41] consistent with rates of inadequate follow-upwards in a non-primary care setting (28%) [46]. Nevertheless, failure to attend half-dozen-monthfollow-upwards was significantly higher in the Dutch-based study at 71.6%, [26] which may reflect the reduced role of PCPs in the breast cancer screening regimen in the Netherlands where women are invited for mammogram via nationwide screening programs and PCPs but go involved when the women receives an aberrant effect [9]. Failure to attend immediate follow-upwards (within 3 months) for high risk mammograms (BIRADS®- four,-5,-0) in Us-based studies was too lower (7.2–33%) [21, 25]. Similarly, patients presenting with breast symptoms, [22, 38] extremely dense tissue, [22] or a family unit history of chest cancer, [19, 27] were more likely to receive adequate follow-upward, consistent with studies in non-main care settings [47,48,49]. Collectively, these findings suggest providers and/or patients prioritise follow-upward in higher run a risk patients. Yet, making comparisons between rates of inadequate follow-up across included studies was difficult, particularly over time, due to inconsistencies in definitions of inadequate follow-up, fourth dimension intervals examined, written report design, populations studied and primary care settings across studies.

Private patient-, PCP- and health organisation-relatedfactors were found to influence aberrant mammogram follow-up. In particular, women of ethnic minority (African-American, [21] and Asian women) [19] were less likely to have adequate follow-up in primary intendance. Kaplan et al. also establish Latina women in principal care with breast symptoms or an abnormal mammogram (examined collectively, therefore excluded from this review) were less likely to have acceptable follow-upward, [50] and these discrepancies in the follow-upward of indigenous minority women have been found to extend across main care settings to hospital and other not-primary care facilities [51, 52]. Further, given the persistent disparities in afterward phase breast cancer diagnoses and increased mortality in African-American and Latina women reported beyond several studies, [53,54,55] identifying and addressing barriers to the suboptimal follow-upwards of abnormal mammograms in these populations is imperative in order to improve breast cancer outcomes.

Women with lower education attainment (≤high schoolhouse graduation) were less likely to receive adequate follow-up in primary care [19, 27]. Moreover, a report examining patient'south understanding of abnormal mammogram results by Karliner et al. found lower education attainment may translate to reduced understanding of the implications of aberrant mammogram results and/or the need for follow-upwards in some women [56]. Further to this, Yabroff et al. suggested measures to assess abnormal mammogram comprehension and health literacy in women were likely to be beneficial in increasing healthcare utilisation by women [27]. Given lower education attainment has been found to contribute to later stage chest cancer diagnoses, [57, 58] addressing this barrier could improve patient outcomes.

While several studies found women > 50 years were more likely to have adequate follow-upwards, [19, 22,23,24, 27] findings were conflicted [nineteen, 35]. Studies not included in this review plant inconsistencies between age and aberrant mammogram follow-up: Haas et al. found timely follow-up of abnormal screening or diagnostic mammograms was higher in women > 50 years [59]; whereas Kaplan et al. plant historic period was not a significant predictor of follow-up in women with breast symptoms and/or an abnormal mammogram (examined collectively) [50]. Although the probability that an abnormal mammogram is due to breast cancer increases with age, especially after the historic period of 50, [60] this observation raises concerns about potential breast cancer diagnosis delays in younger women.

Several of import psychological barriers preventing women from attending follow-upwardly, including fear of pain or cancer, [17, xl] pain/embarrassment, [17, 21, 26] and fatalistic behavior, [17] were identified. Similar barriers have been found in women with inadequate follow-upwardly in not-principal intendance settings, [49] and in women with abnormal mammogram/chest symptoms (examined collectively) in master care [61]. Moreover, fear of diagnostic procedures preventing timely follow-upwards has been plant in women with aberrant cervical screening results, [62] and patients with positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) results [63].

Evidence suggests improved PCP-patient communication may help overcome patient-related barriers to follow-up in primary intendance and in turn, amend patient outcomes. In item, several included studies highlighted that effective PCP-patient advice was key to ensuring women understood their aberrant mammogram results and the need for follow-upward, [17, 24, xl] consistent with other studies non included in this review [64, 65]. Further, Kerner et al. found African-American women with an abnormal mammogram that had open dialogue with their doctor and received clear data nearly recommended follow-up procedures were more than likely to accept adequate follow-up across primary and not-primary care [46].

Patient navigator interventions take been found to exist effective at addressing patient-related barriers and improving follow-upwards. Battaglia et al. constitute patient navigation alone improved timely follow-up in low-income and ethnic minority women with an abnormal mammogram in main care, [66] all the same, this study was not included as inadequate follow-upward was not specifically addressed. The RCT by Ferrante et al. found women with an abnormal mammogram receiving navigated care in non-primary care not only had improved follow-up, simply also reported less feet and increased satisfaction with their follow-up intendance [67]. Further, navigated care was plant to exist associated with reduced stages of breast and cervical cancer diagnoses [68].

One included RCT by Ell et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of patient navigation with example direction and increased PCP-patient educational activity and counselling (the SAFe intervention) in improving follow-upwards in indigenous minority women in primary care [34]. This intervention and like models were found to increase abnormal mammogram follow-up in depression-income women in not-primary intendance settings [69, 70]. In particular, the RCT by Maxwell et al. found patient navigation that included emotional support, translation and assist with overcoming barriers to assessing follow-upwards effectively improved follow-up in Korean American women attending non-primary care screening centres across California [71]. Further, Llovet et al. indicated the potential of patient navigation and improved PCP-patient communication to accost miscommunication of FOBT+ results and fears of diagnostic procedures [63]. Collectively these findings indicate further studies examining these models in abnormal mammogram follow-up in chief intendance are warranted to test this approach, especially in indigenous minority women, and examine patient satisfaction and price-effectiveness [72].

Two included studies illustrated the effectiveness of clinician reminder alerts or alerts to amend abnormal mammogram follow-upwards in primary intendance [26, 37]. Withal, inside EHR-based systems, Casalino et al. and Smith et al. found "alert" notifications of a drove of abnormal exam results in primary care created information overload due to notifications containing both examination results and clinical procedures/policies which in turn contributed to inadequate follow-up [36, 39]. Consequent with these findings, studies beyond nationwide Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities, [73] and in a not-main care VA outpatient setting, [74] not included in this review also institute PCPs perceived alerts created information overload due the extent of unrelated information sent with examination results. Moreover, Hysong et al. and Singh et al. found PCPs perceived that automated EHR alerts would be more efficient if PCPs managed their own alerts so patient'south test results were received in a separate alert from clinical management information and the corporeality of clinical information received could likewise be reduced to decrease notification overload [73, 74]. Despite these limitations, Al-Mutairi et al. found just 7.seven% of abnormal imagining results, including one abnormal mammogram, were "lost to follow-upward" within 4 weeks within a large VA convalescent clinic with automated EHR-based alerts [75].

Farther barriers identified by PCPs included the absence of a reliable method in place to place patients defaulting follow-upwardly, [25] and PCPs' difficulty accessing patient records, [26] that need to addressed in society to better abnormal follow-up in principal care. Farther, Casalino et al. and Smith et al. plant PCPs perceived dubiety surrounding their part and responsibility in aberrant mammogram follow-up beyond dissimilar healthcare platforms and with different providers also contributed to inadequate follow-up [36, 39]. Consistent with these findings, another study examining the follow-upward of a collection of convalescent test results plant PCPs perceived having "no system in place as a reminder", "insufficient retrieval systems" or uncertainty of responsibility contributed to delayed follow-upward, [76] however, the failure to delineate abnormal mammogram follow-upward precluded this study from review. Singh et al. found the absence of standard protocols and procedures in place to manage the follow-upward of results was responsible for the inadequate follow-upwards of abnormal radiology results within an EHR-based main intendance system [77]. PCPs perceived improved display, sorting and visualisation of exam results within EHR-based alert notifications, that included assigning and displaying who was responsible for follow-up, was needed to improve both the advice and management of test results [73, 74].

Logistical barriers preventing women from accessing follow-upwardly identified, including unavailable medical appointment times, [17, 18, 40] and childcare bug, [17, xl] will need to be addressed to meliorate abnormal mammogram follow-up. While 2 RCTs non included in this review indicated that follow-up could be improved if the office of patient navigators included overcoming barriers related to inappropriate engagement scheduling at screening clinics, [71] and in hospital settings, [78] it is likely that changes at an institutional level volition also be required to increment access to follow-up. For instance, increasing availability of follow-upcare to evenings and weekends could accommodate women with full-time employment or childcare demands.

This review constitute the resource offered by managed care insurance translated to improved follow-upwardly in these women, [24] consistent with some other study examining aberrant and screening mammogram follow-up collectively [59]. However, nosotros found other forms of private wellness insurance did not influence follow-up [17, 21, 27, 37]. Reported advantages of managed intendance including consistent care, [59] and access to more resources or/and less barriers than women without insurance or other forms of insurance, [67, 79] further reinforces the benefits of added support systems in identify to improve abnormal mammogram follow-upward.

Study strengths include our rigorous systematic review methodology and comprehensive overview of barriers and/or facilitators associated with abnormal mammogram follow-upwards in primary care. Strict exclusion and inclusion criteria ensured only studies specifically examining inadequate follow-upwardly were included in the review. Moreover, all study findings and outcomes were reported from studies relevant to inadequate follow-up in chief intendance. Later, due to the stringent methodology used, we do not believe this review is discipline to selection bias.

Due to heterogeneity in study measures, a narrative review was performed. Additionally, this heterogeneity prevented a feasible evaluation of potential publication bias by quantitative methodology using measures such every bit wood plots. Afterwards, it can only be postulated as to whether this review was subject to publication bias. That is, there may exist bias towards publishing papers that report high rates of inadequate follow-up as these papers highlight the extent of suboptimal aberrant mammogram follow-upwards in primary care and are clinically relevant to patient intendance. Conversely, bias to publishing studies with low rates of inadequate follow-up may also occur as these papers assistance validate breast cancer screening (and abnormal mammogram follow-up) in a primary care setting.

Further, the review was limited by the quality of included studies, with one report at loftier risk of bias and vii studies at moderate take chances. The level of show to support factors associated with follow-up as well varied. Some studies based findings on self-reported surveys to study PCP and patient perceptions which are subject field to remember and/or responder bias and may affect the external reliability of these findings [26, 39, 40]. Other studies used judicious analyses to examine associations and used advisable methods to select for relevant variables to include in multivariable models, [18, 21, 23, 24, 27, 35, 37] with others adjusting for potentially inappropriate variables in analyses [nineteen, 22, 25]. Moreover, some studies were conducted in large institutions, [17, 21, 34, 37] with others in pocket-sized clinics, [36] and beyond both settings [18, 25]. In studies conducted across both public and private facilities, it was also difficult to make up one's mind the extent conducted in a primary care setting, however, the decision was fabricated to exclude studies performed < fourscore% in principal intendance.

A further report limitation included the generalizability of written report findings to countries outside of the U.s.a. as all studies with the exception of one Dutch-based study published in 1998 were conducted in the U.s.a. which has unique primary and ambulatory care systems and study populations in terms of ethnicity and socioeconomic condition. Further, PCPs in the United states are straight involved in promoting breast cancer screening and referring patients for mammograms, as well every bit organising the follow-up of abnormal mammograms, [80] whereas several developed countries throughout Europe, [81, 82] and in Canada, [12] and Commonwealth of australia, [82] have implemented population-based organized or opportunistic chest cancer screening programs, with invitations for abnormal mammogram follow-up occurring predominantly via automated fail-prophylactic mechanisms. Afterward, chest cancer screening outside the US is less reliant on primary intendance for aberrant mammograms follow-upward and PCP involvement. Moreover, the relevance of report findings to countries with formalised breast screening programs that operate in parallel to primary care, is also unclear.

Conclusions

Narrative systematic review predominantly highlighted the suboptimal follow-up of abnormal mammograms in primary care in the U.s.a., potentially compromising benefits of breast cancer screening. While EHR-enabled tracking and reminder alerts were demonstrated to be constructive in follow-up, patient navigation and case direction, with increased PCP-patient communication, may improve follow-upward. Additionally, PCP-customisation of alerts, greater accessibility to patient records, and clarifying PCPs' roles and responsibilities in the follow-upwardly procedure, and minimising logistical barriers to accessing care such as inconvenient dispensary hours are warranted. Overall, addressing factors contributing to inadequate follow-upwards with targeted interventions, peculiarly in subgroups of women near at risk (ethnic minority and less educated women) could potentially optimize abnormal mammogram follow-up in primary care and improve patient outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

All information generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary data files.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Radiology

- aHR:

-

Adapted Take chances Ratio

- aOR:

-

Adapted Odds Ratio

- BIRADS®:

-

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System®

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- Hr:

-

Hazard Ratio

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- PCP:

-

Primary care provider

- RCT:

-

Randomised control trial

- SAFe:

-

Screening Adherence Follow-up

References

-

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/ten.3322/caac.21492.

-

Myers ER, Moorman P, Gierisch JM, Havrilesky LJ, Grimm LJ, Ghate Due south, et al. Benefits and harms of breast Cancer screening: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1615–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.13183.

-

Hendrick RE, Helvie MA. Mammography screening: a new guess of number needed to screen to forbid one breast cancer death. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(three):723–viii. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.11.7146.

-

Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Dear SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with chest cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353(9159):1119–26. https://doi.org/x.1016/S0140-6736(99)02143-1.

-

Kothari A, Fentiman IS. 22. Diagnostic delays in breast cancer and bear upon on survival. Int J Clin Pract. 2003;57(iii):200–3.

-

Haas J, Kaplan C, McMillan A, Esserman LJ. Does timely cess affect the anxiety associated with an abnormal mammogram outcome? J Womens Wellness Gend Based Med. 2001;x(half-dozen):599–605. https://doi.org/10.1089/15246090152543184.

-

Radiology ACo: American Higher of Radiology. ACR Practice Parameter for the performance of screening and diagnostic mammography. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/Screen-Diag-Mammo.pdf Adopted 2018 (Resolution 36): Philadelphia, PA, USA (accessed 29 April, 2020). 2018.

-

Dimitrova N, Parkinson ZS, Bramesfeld A, Ulutürk A, Bocchi G, López-Alcalde J, Pylkkanen L, Neamțiu L, Ambrosio Thousand, Deandrea Southward et al: European Guidelines for Chest Cancer Screening and Diagnosis - the European Breast Guidelines https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.european union/repository/bitstream/JRC104007/european%20breast%20guidelines%20report%20(online)%twenty(non-secured).pdf, accessed 29 August 2020. 2016.

-

RIVM: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, kingdom of the netherlands. https://world wide web.rivm.nl/en/breast-cancer-screening-programme/process (updated xi/02/2018), accessed 22 August 2020.

-

BreastScreen: BreastScreen Australia information dictionary Version 1.two https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/41f63713-2785-4511-9854-f31885071018/aihwcan127.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed iv Baronial 2020).

-

Eberl MM, Pull a fast one on CH, Edge SB, Carter CA, Mahoney MC. BI-RADS classification for management of abnormal mammograms. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(2):161–4. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.19.2.161.

-

Katz SJ, Zemencuk JK, Hofer TP. Chest cancer screening in the U.s. and Canada, 1994: socioeconomic gradients persist. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(5):799–803. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.90.five.799.

-

Stamler LL, Thomas B, Lafreniere One thousand. Working women identify influences and obstacles to breast health practices. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27(5):835–42.

-

Selby K, Bartlett-Esquilant G, Cornuz J. Personalized cancer screening: helping main intendance rise to the challenge. Public Health Rev. 2018;39(1):four. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0083-x.

-

Grumbach M, Selby JV, Damberg C, Bindman AB, Quesenberry C Jr, Truman A, et al. Resolving the gatekeeper conundrum: what patients value in principal intendance and referrals to specialists. JAMA. 1999;282(3):261–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.three.261.

-

Schootman M, Jeff DB, Gillanders WE, Yan Y, Jenkins B, Aft R. Geographic clustering of adequate diagnostic follow-up after abnormal screening results for breast cancer amid low-income women in Missouri. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(nine):704–12. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.017.

-

Rojas M, Mandelblatt J, Cagney K, Kerner J, Freeman H. Barriers to follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms among low-income minority women. Cancer control Center of Harlem. Ethn Wellness. 1996;one(3):221–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.1996.9961790.

-

McCarthy BD, Yood MU, Janz NK, Boohaker EA, Ward RE, Johnson CC. Evaluation of factors potentially associated with inadequate follow-upwardly of mammographic abnormalities. Cancer. 1996;77(x):2070–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960515)77:10<2070::AID-CNCR16>iii.0.CO;two-South.

-

Nguyen KH, Pasick RJ, Stewart SL, Kerlikowske K, Karliner LS. Disparities in aberrant mammogram follow-up fourth dimension for Asian women compared with non-Hispanic white women and between Asian ethnic groups. Cancer. 2017;123(xviii):3468–75. https://doi.org/ten.1002/cncr.30756.

-

Yabroff KR, Washington KS, Leader A, Neilson E, Mandelblatt J. Is the promise of cancer-screening programs being compromised? Quality of follow-up care after abnormal screening results. Med Intendance Res Rev. 2003;60(3):294–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558703254698.

-

Jones BA, Dailey A, Calvocoressi L, Reams K, Kasl SV, Lee C, et al. Inadequate follow-upwards of abnormal screening mammograms: findings from the race differences in screening mammography procedure written report (U.s.a.). Cancer Causes Command. 2005;16(7):809–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-005-2905-7.

-

Wernli KJ, Aiello Bowles EJ, Haneuse Southward, Elmore JG, Buist DS. Timing of follow-up later aberrant screening and diagnostic mammograms. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(2):162–vii.

-

Webber PA, Fox P, Zhang X, Pond M. An test of differential follow-upwardly rates in breast cancer screening. J Commun Wellness. 1996;21(2):123–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01682303.

-

Poon EG, Haas JS, Louise Puopolo A, Gandhi TK, Burdick E, Bates DW, et al. Communication factors in the follow-upwards of abnormal mammograms. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):316–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30357.x.

-

McCarthy BD, Yood MU, Boohaker EA, Ward RE, Rebner M, Johnson CC. Inadequate follow-up of aberrant mammograms. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12(four):282–8. https://doi.org/ten.1016/S0749-3797(18)30326-X.

-

Duijm LE, Zaat JO, Guit GL. Nonpalpable, probably benign breast lesions in general practice: the part of follow-up mammography. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(432):1421–3.

-

Yabroff KR, Breen N, Vernon SW, Meissner HI, Freedman AN, Ballard-Barbash R. What factors are associated with diagnostic follow-up after abnormal mammograms? Findings from a U.S. National Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13(5):723–32.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA argument. Int J Surg. 2010;8(five):336–41. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007.

-

Cochrane Constructive Practice and System of Care (EPOC). Screening deamI: EPOC resources for review authors, 2017. https://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors (accessed 6 February 2020).

-

Institute JB: Joanna Briggs Found reviewers' manual: 2014 edition. . Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual: 2014 edition 2014.

-

Institute JB: Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual: 2014 edition Adelaide, Australia 2014, https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools (accessed 23 March 2020).

-

Chima Southward, Reece JC, Milley G, Milton South, McIntosh JG, Emery JD. Conclusion support tools to improve cancer diagnostic decision making in principal care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(689):e809–18. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X706745.

-

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or not-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

-

Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Xie B. Patient navigation and case direction following an abnormal mammogram: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44(1):26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001.

-

Burack RC, Simon MS, Stano M, George J, Coombs J. Follow-up among women with an abnormal mammogram in an HMO: is it consummate, timely, and efficient? Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(10):1102–13.

-

Casalino LP, Dunham D, Mentum MH, Bielang R, Kistner EO, Karrison TG, et al. Frequency of failure to inform patients of clinically significant outpatient test results. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1123–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.130.

-

Grossman Eastward, Phillips RS, Weingart SN. Performance of a fail-safe system to follow up abnormal mammograms in primary care. J Pat Saf. 2010;6(three):172–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181efe30a.

-

Schootman Grand, Myers-Geadelmann J, Fuortes L. Factors associated with adequacy of diagnostic workup subsequently abnormal breast cancer screening results. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13(two):94–100. https://doi.org/10.3122/15572625-13-ii-94.

-

Smith MW, Hughes AM, Brown C, Russo, Giardina TD, Mehta P, et al. Examination results management and distributed knowledge in electronic health record-enabled primary care. Wellness Inform J. 2018:1460458218779114.

-

Allen JD, Shelton RC, Harden Eastward, Goldman RE. Follow-up of aberrant screening mammograms among low-income ethnically diverse women: findings from a qualitative written report. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(two):283–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.024.

-

Poon EG, Gandhi TK, Sequist TD, Murff HJ, Karson Equally, Bates DW. "I wish I had seen this examination result before!": dissatisfaction with test result direction systems in primary intendance. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2223–viii. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.20.2223.

-

D'Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA. ACR BI-RADS Atlas: breast imaging re-porting and information arrangement. Reston: American College of Radiology; 2013.

-

Bruening W, Fontanarosa J, Tipton K, Treadwell JR, Launders J, Schoelles K. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of core-needle and open surgical biopsy to diagnose breast lesions. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):238–46. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-ane-201001050-00190.

-

Lameijer JRC, Voogd Ac, Broeders MJM, Pijnappel RM, Setz-Pels Due west, Strobbe LJ, et al. Trends in delayed breast cancer diagnosis after remember at screening mammography. Eur J Radiol. 2021;136:109517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109517.

-

Nickson C, Mason KE, English DR, Kavanagh AM. Mammographic screening and chest cancer mortality: a case-control written report and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2012;21(ix):1479–88. https://doi.org/ten.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0468.

-

Kerner JF, Yedidia M, Padgett D, Muth B, Washington KS, Tefft M, et al. Realizing the promise of breast cancer screening: clinical follow-upwards later on abnormal screening amidst black women. Prev Med. 2003;37(2):92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00087-2.

-

Caplan LS, May DS, Richardson LC. Time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: results from the National Breast and cervical Cancer early detection program, 1991-1995. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(i):130–four. https://doi.org/ten.2105/ajph.90.ane.130.

-

Ramirez AJ, Westcombe AM, Burgess CC, Sutton Southward, Littlejohns P, Richards MA. Factors predicting delayed presentation of symptomatic breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353(9159):1127–31. https://doi.org/x.1016/S0140-6736(99)02142-10.

-

Arndt 5, Sturmer T, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Dhom G, Brenner H. Patient delay and phase of diagnosis amongst chest cancer patients in Germany -- a population based written report. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(7):1034–40. https://doi.org/x.1038/sj.bjc.6600209.

-

Kaplan CP, Crane LA, Stewart S, Juarez-Reyes M. Factors affecting follow-upward amidst low-income women with breast abnormalities. J Women's Wellness (Larchmt). 2004;13(2):195–206. https://doi.org/10.1089/154099904322966182.

-

Chang SW, Kerlikowske K, Napoles-Springer A, Posner SF, Sickles EA, Perez-Stable EJ. Racial differences in timeliness of follow-up after abnormal screening mammography. Cancer. 1996;78(seven):1395–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961001)78:vii<1395::Assistance-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-1000.

-

Strzelczyk JJ, Dignan MB. Disparities in adherence to recommended followup on screening mammography: interaction of sociodemographic factors. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(1):77–86.

-

Hirschman J, Whitman S, Ansell D. The black:white disparity in breast cancer mortality: the instance of Chicago. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(three):323–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0102-y.

-

Hunt BR, Whitman S, Hurlbert MS. Increasing black:white disparities in breast cancer bloodshed in the fifty largest cities in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38(2):118–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2013.09.009.

-

Goel MS, Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, Phillips RS. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;eighteen(12):1028–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.20807.10.

-

Karliner LS, Ma L, Hofmann M, Kerlikowske K. Linguistic communication barriers, location of care, and delays in follow-upwards of abnormal mammograms. Med Care. 2012;50(ii):171–viii. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822dcf2d.

-

Taplin SH, Ichikawa Fifty, Yood MU, Manos MM, Geiger AM, Weinmann South, et al. Reason for tardily-stage chest cancer: absence of screening or detection, or breakup in follow-up? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(20):1518–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djh284.

-

Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, Macdonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: show for common cancers. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(Suppl 2):S92–S101. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605398.

-

Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Brennan TA. Differences in the quality of intendance for women with an abnormal mammogram or breast complaint. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;xv(5):321–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08030.x.

-

Brown ML, Houn F, Sickles EA, Kessler LG. Screening mammography in community practice: positive predictive value of abnormal findings and yield of follow-upwards diagnostic procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(6):1373–seven. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.165.6.7484568.

-

Kaplan CP, Eisenberg M, Erickson PI, Crane LA, Duffey S. Barriers to breast abnormality follow-upwards: minority, depression-income patients' and their providers' view. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4):720–6.

-

Percac-Lima Due south, Aldrich LS, Gamba GB, Bearse AM, Atlas SJ. Barriers to follow-upwardly of an aberrant pap smear in Latina women referred for colposcopy. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(xi):1198–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1450-6.

-

Llovet D, Repose M, Conn LG, Bravo CA, McCurdy BR, Dube C, et al. Reasons for lack of follow-up colonoscopy among persons with a positive fecal occult blood test result: a qualitative study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(12):1872–lxxx. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0381-four.

-

Karliner LS, Patricia Kaplan C, Juarbe T, Pasick R, Perez-Stable EJ. Poor patient comprehension of abnormal mammography results. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(5):432–vii. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40281.x.

-

Poon EG, Kachalia A, Puopolo AL, Gandhi TK, Studdert DM. Cognitive errors and logistical breakdowns contributing to missed and delayed diagnoses of breast and colorectal cancers: a procedure analysis of closed malpractice claims. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(eleven):1416–23. https://doi.org/x.1007/s11606-012-2107-iv.

-

Battaglia TA, Roloff 1000, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. A patient navigation intervention. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):359–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22354.

-

Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health. 2008;85(1):114–24. https://doi.org/x.1007/s11524-007-9228-ix.

-

Battaglia TA, Bak SM, Heeren T, Chen CA, Kalish R, Tringale S, et al. Boston patient navigation research program: the impact of navigation on fourth dimension to diagnostic resolution after abnormal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2012;21(10):1645–54. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0532.

-

Ell K, Padgett D, Vourlekis B, Nissly J, Pineda D, Sarabia O, et al. Abnormal mammogram follow-upward: a pilot report women with low income. Cancer Pract. 2002;x(three):130–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.103009.10.

-

Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-upwardly amid the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19–xxx.

-

Maxwell AE, Jo AM, Crespi CM, Sudan M, Bastani R. Peer navigation improves diagnostic follow-upward afterward breast cancer screening among Korean American women: results of a randomized trial. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(11):1931–forty. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9621-vii.

-

Lee JH, Fulp W, Wells KJ, Meade CD, Calcano E, Roetzheim R. Patient navigation and time to diagnostic resolution: results for a cluster randomized trial evaluating the efficacy of patient navigation among patients with breast cancer screening abnormalities, Tampa, FL. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74542. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pone.0074542.

-

Singh H, Spitzmueller C, Petersen NJ, Sawhney MK, Smith MW, Murphy DR, et al. Primary intendance practitioners' views on test result management in EHR-enabled health systems: a national survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;xx(4):727–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001267.

-

Hysong SJ, Sawhney MK, Wilson L, Sittig DF, Esquivel A, Singh Southward, et al. Understanding the direction of electronic test event notifications in the outpatient setting. BMC Med Inform Dec Mak. 2011;11(1):22. https://doi.org/ten.1186/1472-6947-11-22.

-

Al-Mutairi A, Meyer AN, Chang P, Singh H. Lack of timely follow-upwards of abnormal imaging results and radiologists' recommendations. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(four):385–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2014.09.031.

-

Moore C, Saigh O, Trikha A, Lin JJ. Timely follow-upward of abnormal outpatient test results: perceived barriers and impact on patient safety. J Pat Saf. 2008;4(iv):241–four. https://doi.org/ten.1097/PTS.0b013e31818d1ca4.

-

Singh H, Arora HS, Vij MS, Rao R, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Communication outcomes of critical imaging results in a computerized notification system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(4):459–66. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M2280.

-

Tejeda S, Darnell JS, Cho YI, Stolley MR, Markossian TW, Calhoun EA. Patient barriers to follow-up care for breast and cervical cancer abnormalities. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(six):507–17. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.3590.

-

Ferrante JM, Rovi Southward, Das Chiliad, Kim S. Family physicians expedite diagnosis of breast affliction in urban minority women. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(1):52–9. https://doi.org/x.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060117.

-

Taplin SH, Taylor V, Montano D, Chinn R, Urban N. Specialty differences and the ordering of screening mammography by primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1994;7(5):375–86.

-

Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Benbrahim-Tallaa Fifty, Bouvard 5, Bianchini F, et al. International Agency for Enquiry on Cancer handbook working M: breast-cancer screening--viewpoint of the IARC working group. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2353–eight. https://doi.org/ten.1056/NEJMsr1504363.

-

Basu P, Ponti A, Anttila A, Ronco M, Senore C, Vale DB, et al. Condition of implementation and organisation of cancer screening in the European Marriage member states-summary results from the second European screening written report. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(1):44–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31043.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jim Berryman from the University of Melbourne Library for his valuable assistance in the systematic review literature search.

Disclaimer

None

Funding

Jeanette C Reece is supported past a National Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Peter Doherty early career research fellowship (APP1120081). Jon D Emery was supported by a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship and is a member of the senior kinesthesia of the multi-institutional CanTest Collaborative, which is funded past Cancer Enquiry United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland (C8640/A23385). Eleanor F One thousand Neal holds an Australian Government Research Training Programme (RTP) Scholarship. Peter Nguyen holds an Australian Government RTP Scholarship, University of Melbourne Graduate Inquiry Access Scholarship and Margaret and Irene Stewardson Fund Scholarship.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

Study plan and design: J.C.R., P.Due north. and J.D.East. Screening of titles and abstracts: J.C.R. and P.N. Extraction of data: J.C.R and E.F.G.N. Assay and interpretation of information: J.C.R., Due east.F.Grand.Northward., J.G.M. and J.D.E. Writing of manuscript: J.C.R. Review and approval of manuscript: J.C.R., E.F.G.Due north., P.N., J.G.M. and J.D.E. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ideals blessing and consent to participate

Ethical approval or consent was non required for this systematic review as data were acquired from published studies.

Consent for publication

Non applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as yous give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and bespeak if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this commodity are included in the article's Creative Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If cloth is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/goose egg/i.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reece, J.C., Neal, East.F.Yard., Nguyen, P. et al. Delayed or failure to follow-up abnormal breast cancer screening mammograms in primary intendance: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 21, 373 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08100-iii

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08100-3

Keywords

- Primary care

- Chest cancer screening

- Abnormal mammogram

- Inadequate follow-upwards

Source: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-021-08100-3

0 Response to "what are the repercussions for physicians to follow up on screening mammograms"

Post a Comment